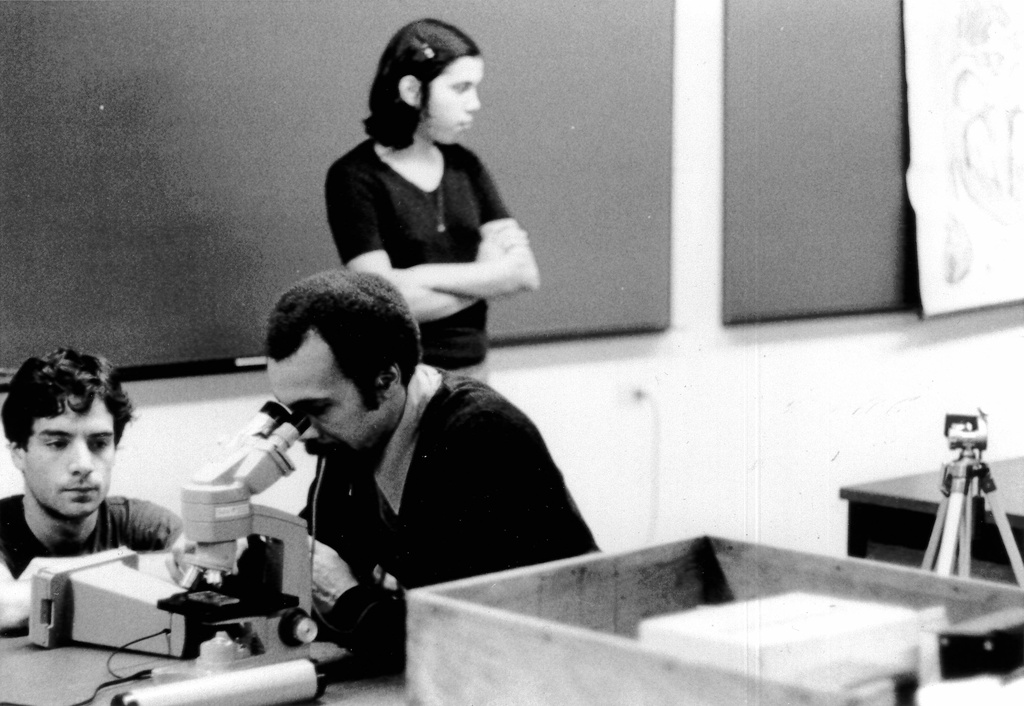

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves in the Lab, c. 1970s. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Milford Graves’s home laboratory is also a modern-day curiosity cabinet filled with the tools of several trades and artifacts from around the world. Abstract and vibrantly colored murals decorate the walls; hand-altered drum sets are strewn here and there; herbs in labeled jars line up evenly across bar tops; scrolls featuring anatomical drawings can be pulled down from the ceiling; and medical equipment is everywhere, particularly diagnostic systems like physiographs, which are used to measure an individual’s heart rate, respiration, skin response, and blood pressure.

Beyond being a pioneer of the Free Jazz movement and a celebrated percussionist, Graves dedicated his life to a critical investigation of heart rhythms and the scientific study of vibrations. He even trained to become a medical laboratory technician, after which, he worked for two years as a laboratory assistant in a veterinarian's office. In the months prior to starting his technician course, Graves had been offered gigs with US trumpeter Miles Davis and South African singer Miriam Makeba—his talents were widely known in the global musical community.[1]But he instead decided to pursue another passion, one that deepened his knowledge of science but also complemented his philosophies as a musician.

Graves believed fervently in embracing “fundamental” or “total” sound. When preparing to perform for a large crowd, he would plant himself near the audience and listen intently to the people—their laughs, the banter— to understand the “grand fundamental tone.” If the energy was positive, he would feed it back to them through the music, but on a higher, amplified plane. If it was negative, he would adjust the energy and project a different sound to the crowd—a strategy that he would later use in his computer-generated studies around heart rhythms and his decades-long quest to find the healthy vibrations of an individual’s heartbeat.[2]

Graves studied variations of rhythms, pulseology, and vibration not only on a scientific level, but on a spiritual plane that drew upon Chinese medicine, African traditions, and other global holistic knowledges. One famous story from 1975 has him roaming the aisles of the medical section at a Barnes and Nobles bookstore in New York and coming across a double LP of stethoscopic heart recordings (beats, murmurs, and arrhythmias) produced by Dr. George David Geckler for “beginners in auscultatory diagnosis,” or complications of the heart. Graves stated, “When I went home and listened to it, I could hear traditional African drum rhythms in heart sounds. . . . These pathological heart sounds were like rhythms that a drummer gets into in a state of possession."[3] The sounds on the recordings were familiar. Graves had studied drum rhythms from West Africa to Haiti, which foregrounded sounds that were reminiscent of the recordings but also that expanded upon them.

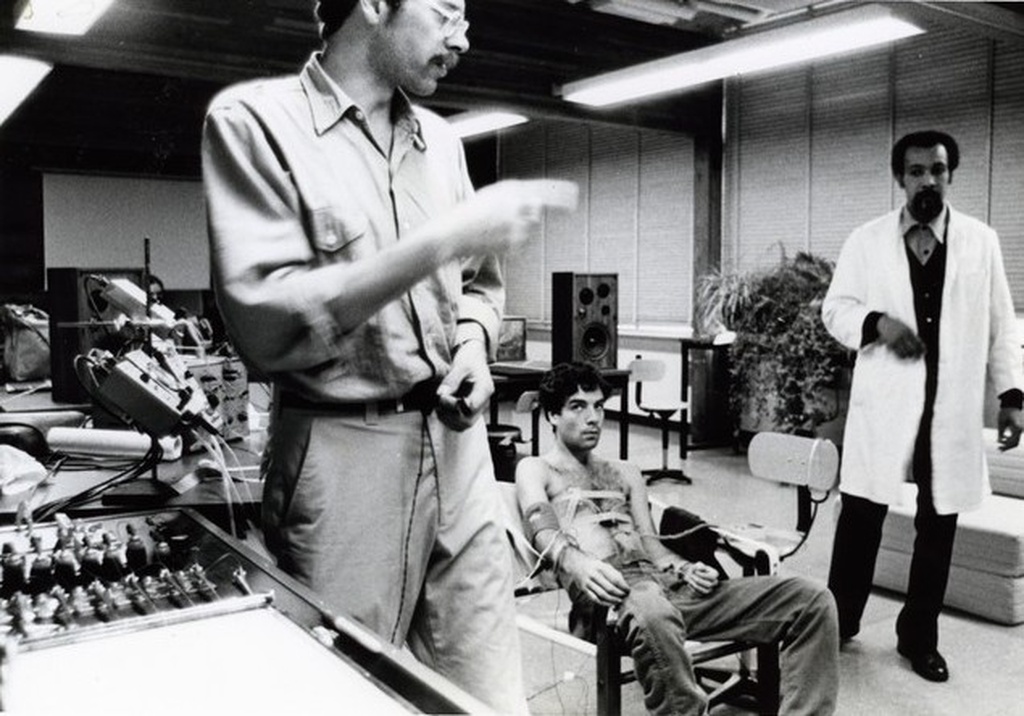

After his years as a technician, Graves was offered a faculty position at Bennington College, and he taught there for more than forty years. There he would host research sessions around heart rhythms—most famously in what he called the “Institute of Bio Creative Intuitive Music,” in which he would connect students to EKG machines, tape a stethoscope over their hearts, and attach electrical sensors to their wrists and legs, then play "spontaneously improvised music” (a combination of live and prerecorded sounds) and observe the reactions. Graves gathered data from both muscular and electrical responses: the stethoscope monitors the sound of the heart valves opening and closing, while the other sensors detect the electrical impulses that cause the heart to beat.[4]

In the early 2000s Graves further built out his home laboratory. He ordered a custom-designed stethoscope with a wider frequency range and began to use and manipulate LabVIEW, a highly adaptable engineering software and development system.[5] Graves created a program that allowed him to extract musical melodies from the heart, and manifest them in a customized visual interface that includes wave and line graphs as well as digital illustrations and animations—these would later become core elements in the multimedia sculptural works Graves created in the last years of his life.

While some traditional medical practitioners may be skeptical of this kind of experimental research, Graves's contribution to the scientific field has been felt by many. Some scientists have credited Graves with discovering variable heart rate (VHR), a concept related to micropatterning within our heartbeats.[6] Prior to his passing Graves was working alongside cardiologist and microbiologist Carlo Ventura to investigate how vibrations stimulate growth in stem cells and how the variable rhythms that he was so knowledgeable about could speed the process yet more.

[1] "Profile: Medical Research into the Sound of the Human Heart." National Public Radio, February 28, 2005.

[2] Jason Gross interview with Milford Graves. Perfect Sound Forever, 1998.

[3] "Healed by the Beat" (Milford Graves and Jean-Daniel Lafontant in conversation with Jake Nussbaum and Catherine Despont) Intercourse Magazine, no. 5 (June 2017): 119.

[4] "Profile: Medical Research into the Sound of the Human Heart."

[5] For example, some environmentalists use LabVIEW to build regulatory systems capable of monitoring gas and energy levels, and certain stethoscopes and other detecting devices are made specifically to work with LabVIEW.

[6] "Healed by the Beat," 118.

Heartbeat Drummer, 2004. Reuters, color video, 4:19 minutes. Courtesy the Estate of Milford Graves.

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves in the Lab, c. 1970s. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Milford Graves, LabVIEW animation, c. 2014-2020. LabView software screen captures, 4:21 minutes. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Milford Graves, LabVIEW animation, c. 2014-2020. LabView software screen captures, 2:53 minutes. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Milford Graves, LabVIEW animation, c. 2014-2020. LabView software screen captures, 4:32 minutes. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves in the Lab, c. 1970s. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.