Photographer unknown, Milford Graves arrives in Japan, 1977. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

In 1977, Milford Graves took his first trip to Japan at the invitation of influential Japanese producer and music critic Aquirax Aida. Perhaps best known for producing Free Jazz artists like Kaoru Abe, Aida frequently promoted tours of Japan for New York artists like Graves and Steve Lacy and European artist Derek Bailey. Spending nearly a month in Japan, Graves not only recorded the seminal album Meditation Among Us but also became the subject of an extensive two-volume feature of writing and documentation in Jazz Magazine. Originally published in the second volume of this special Jazz Magazine series, the text below was composed by Aida and built from Milford Graves’s statements. Translated by Yuzo Sakuramoto on the occasion of Milford Graves: Fundamental Frequency, this chapter makes a significant portion of Aida’s text available to English-language audiences for the first time. Featured alongside this revelatory new translation, this segment includes a compilation of videos, archival photographs, and text documenting Graves’s relationship to Japan and his ongoing collaborations with many Japanese artists from improviser Min Tanaka to experimental musician Toshi Tsuchitori.

___

Towards Spontaneous Music and Open Human Relations of Milford Graves

Jazz Magazine, "Milford Graves Collected," 1977, Volume 2

Composed by Aquirax Aida

During his stay in Japan, Milford Graves acted positively and spiritually wherever he went, at all times, and in every situation. He consistently had a positive influence on all with whom he worked. All of us experienced Milford's intensity and vigor, in all of his activities, interactions, and approaches.

His extremely intense, vivid presence and pursuits were always graceful, natural, and delicate without being insistent or imposing, but rather gentle and modest. He was always lucid, always having a clear-cut stance toward everything. In a variety of circumstances, his attitudes and actions were always consistent, without a hint of ambiguity or contradiction. Whoever came into contact with Milford was stunned by his supple and intense, natural and unyielding, determined and unbroken presence. Our amazement at Milford, however, never made us feel uncomfortable, distant or remote; it didn't make us feel difficult or awkward. The more we communicated with him, the more natural we became, feeling his gentleness and modesty, or as one might say, under the influence of his elective affinities and freedom. It was a truly invaluable experience for each of us. Milford certainly had strong vibes and a magnetic force. But they were never exclusive or dismissive in any way. Rather, they were flexible and 'open,' and we could learn through the open and relaxed states we felt when we were with him.

These things were evident in absolutely the same way in his performance as well. His intense vibe and power were incredibly profound, but they were never insular or self-righteous, repelling people, dragging anyone into anything, or ousting anyone. On the contrary, his 'intense power and vibrations,' his 'enormous dynamism' allowed us to unleash our own potential, resilience and naturalness, allowed us to discover a sustainable and continuously open field of encounter that we could share with Milford, and allowed each of us to awaken our 'spontaneity' and 'subjectivity.' The same held true with Milford's austerity. He was strict and lucid about everything, and took a clear stance. However, he never intended to cling exclusively to his own ideas, thereby rejecting different ideas, denying those who were unprepared, or avoiding what he did not understand. Nor did he impose what he believed was right or good, as he was convinced that such action would undermine spontaneities, open relations and subjective interactions. His austerity was thus an expression of his modest, generous and sincere way of life. And he always remained rigorous towards creating rapport, seeking to work more positively and subjectively towards a communality in which each of us took our own initiative.

What he detested the most was egoism and self-seclusion. He occasionally expressed anger about someone's behavior, but that was limited to cases in which the person acted self-righteously or egotistically, denied collaboration, or turned their back on open relationships. No matter how difficult other people's opinions and thoughts were, and how distant they were from his own, he always respected them and tried to accommodate them the best he could if they were acceptable, never adopting a one-sided attitude or denying others completely.

I am writing this because I would like to explain that the statements, judgments, critiques, and strong opinions that are identified in various ways in these conversations with Milford are not arbitrary decisions derived from his obsessions or prejudices, but rather from his free and strong mind. My hope is to let people understand the context of his statements, as well as the basis of the life and attitudes which produced that context. With this in mind, I believe that we are able to encounter the horizon of his open, intense and free mindset.

During a joint practice with Japanese musicians at a camp in Taira City, Milford demonstrated his incredible concentration and sympathy, showing us how he approaches music and performance. When the Japanese musicians were showing off with an excited, aggressive sound particular to free jazz, Milford warned them that culminating the performance in such a way would on the contrary bring down the dynamism of the ensemble. When he performed with some of the players, he also said that, no matter how much the performance changes on the surface, unless it changes fundamentally, musical vitality cannot develop. At every opportunity, Milford made an effort to influence others even more than usual, take more actions and make more comments. Compiled below are the statements he made and things he told us on various occasions during the period of his stay.

●

The basis of the ensemble and the way it should be

Music does not exist only for oneself, and performance does not exist only for one’s own sake. Music and performance always exist within specific human relationships.

Music or performance should be an effort or an action aimed at establishing a collaborative foundation with its own function and life. I always want to perform with great musicians. That is why I rarely play solo except on some special occasions.

Because the creation of an ensemble is indeed the most important element and meaning of music. I believe that the meaning and the role of a specific performance or an ensemble is to create a freer and higher communal relationship in each and every moment and continuously, by understanding one another's characteristics, body movements, feelings and vibrations.

In order to achieve this, first of all, the musicians involved with the ensemble must be spontaneous and self-motivated, and they need to understand their conditions and characteristics. Then they need to understand the vibrations among them. The performance is executed based on these understandings, and the musicians perform in order to develop their own unique qualities or unique feelings subjectively, through mutual interactions, and to establish communal feelings and visions on a higher level between them. Therefore, the goal for each musician is to know their role based on their own spontaneity, and to create even more open relationships among them, rather than asserting themselves or asking everyone for understanding, or deliberately seeking interim understanding.

African music is truly functional and is based on how relationships exist and are understood concretely. In Ghanaian music, ensembles are conducted by musicians with respective roles. Taking the drum ensemble as an example, it is always constituted like a family. There is a drummer in the role of a father, a drummer in the role of a mother, and a drummer in the role of a son. The father establishes a base, the mother embraces it totally and provides volume, and the son provides new changes and ideas. In the actual performance, each drummer voluntarily selects either role according to how they recognize their own disposition and qualities. And these roles can change or be switched as the performance unfolds. A structure like this is not something that is forced by others. It is not self-restraint either, but is accomplished precisely through the spontaneity and freedom of each drummer.

Also, in the music of Congo society, the ensemble is understood as analogous to conversation. One person speaks up, and another person says his or her own opinion succeeding that statement. As others also become engaged with the conversation, subjectivity is maintained, based on the fact that people are together in a common space having a conversation together. And the conversation proceeds as a collaborative one. At this time, if one selfish person starts yelling, asserting their exclusive opinion or ignoring others, ignoring the progress of the conversation, and saying something completely different in an egocentric way, the conversation will not be maintained and will collapse. Meanwhile there are some people who contemplate silently. The important thing here as well is to recognize that this "conversation" is established based on the independence of the members of the ensemble, and that each person is a main actor responsible for the occasion and the progress of the conversation, and also to become aware that there is no conversation to join unless they take concrete actions of their own.

If each person says a different thing and ignores the others, a conversation cannot be established.

I think that the way of looking at the ensemble and the way it exists in Ghana or Congo can be the basis and essence of all ensembles. That means the ensemble is based on the members’ spontaneity and collaborative awareness, and it must also be functional. Without first accomplishing this basic, fundamental type of ensemble, advanced ensembles cannot be established, they are impossible.

Think about the group. Its aim is to elevate the relationship of the members of the group and realize an ensemble that is unique to themselves. Otherwise this group’s existence is meaningless. A truly superb group can only be possible when its members respect each other’s unique qualities. In addition, without mutual respect and commitment among all the performers, the fact of seeking a basis and development and opening up to a higher level as a group will be meaningless.

This is something basic that is not limited to music, but is true with all human relationships when people endeavor to mutually develop and elevate themselves.

And there is no music without an ensemble, and I would like to say, without an open and free ensemble there will be no free and open music. This is why the ensemble has an important role to play in changing human relations, and that is why we can say that music always has a specific possibility in human society.

On Dynamism

I think the idea of original music is a concept. The fact is that there are great musicians who are rooted in themselves, who understand their own uniqueness and are capable of developing and improving it to a higher level. And in order for them to be truly great musicians, they need to understand themselves more deeply than anyone else, to know their own body and sensibility, and be able to display the life force rooted in them. They must be genuinely spontaneous and free in themselves, as well as in their interactions with others, and on top of that, they must be able to materialize their own initiative and subjectivity in performance.

As far as I know, there are hardly any musicians who could be called truly great in this sense.

Some people play music only with their intellect. Some play based only on their feelings. Some rely solely on technical skills. What performers need instead is to integrate and fuse all that is essential within themselves, and perform powerful and free music with all those essential things combined. A person cannot be called a truly independent and creative musician unless their thoughts, mind, body, feeling and technique are all integrated in a natural and inevitable way, and they should be combined and realized within their personality and body. Furthermore, the person must have a position and stance in relation to their own culture and society, a viewpoint or way of living, and a determination as a living being.

And suppose music and performance exist as a form of ensemble, and also exist in specifically collaborative interactions, a musician as an individual—even if they may be right and strong—cannot say that they are open, free and independent, because to be open, free and independent is something that must be established through interacting with others. Therefore collaboration with others is necessary for a performer’s development. In fact, what I call an ensemble is precisely this joint effort. So, it is always necessary to continue interacting and continuing the process together, with other members as your collaborators. This is absolutely essential in order for music to possess true power, true life force.

Up until now, I have met only three friends who can be truly called collaborators. I have never said this to anyone before, but they are Giuseppi Logan, Don Pullen, and Arthur Doyle. Giuseppi lost his mind, Arthur Doyle had nervous breakdowns and went crazy. I could say that even Don was caught by madness. He almost killed his own uniqueness by escaping from his pain, discovering a safe haven in the realm of unfettered senses.

Occasionally I have been told that my collaborators became self-destructive because of my excessive power. I would humbly say that this is not true. They were all really great musicians, however since they tried hard to stay strong by matching my own strength, they failed to become aware of their own unique strength and develop it themselves. It might be said that their efforts to know their own bodies and minds was insufficient. It is more likely for people to destroy themselves than be destroyed by others. Madness comes to you when your tension exceeds the limits of your mind and body. Within madness, you can definitely walk away from this tension. I heard that a friend of mine went to Giuseppi’s house one day, and looking in midair with an empty gaze, he was struggling to imitate my drumming. A week after that Giuseppi lost his mind. I want to say the following to you: when sustainable methods, rooted in the body and mind, for improving and developing yourself to a higher level are not available, it takes forever even for talented and creative musicians to be able to develop their own uniqueness. I started practicing Yara (Note: a form of martial arts Milford invented through integrating Yoruba African martial arts in his own way) and consuming a medical diet (a basis of organic foods) because I thought they were necessary.

In fact, Yara is very beneficial for the foundation of the ensemble I have been talking about, and is deeply connected to my performance. In Yara, which is not intended for fighting or battling, we actually do hit the body of our opponent. Because by being hit on his body, the opponent can experience and learn his own body movements and rhythms. Likewise by hitting my opponent I can also tell his rhythm, vibration and body movements. This kind of discovering each other is very necessary. Learning your own rhythm on your own and understanding the characteristics of your body, as well as understanding the communication between two people through interacting with your opponent is necessary for mutual improvement, and for the ensemble. Yara serves to develop and train the body, at the same time developing the possibilities of the ensemble. Actually I use methods similar to Yara in my performance practice as well. By projecting my vibration towards my opponent, and also sending a specific rhythm to him, I learn his sense of rhythm or vibration, as well as his responsiveness toward other vibrations, in order words, his characteristics. I used this method during practice at the camp as well. The reason I choose this method is clear. An ensemble formulated on responding to the sound emitted is very formulaic and superficial, and responding with sound is too slow to develop a spontaneous performance. I repeatedly told the Japanese musicians to look closely and give their utmost attention, because I wanted to form an ensemble whose performance unfolded by means of reading and feeling the changes of each other’s body movements or vibrations. This is essential to the music I want to realize. Reacting to sound with sound is very ambiguous, and I think it’s too physically-based. When our performance in an ensemble is based on reactions, there is no true spiritual exchange, and the ensemble or music will not achieve an exchange of feelings, and above all, will not lead to truly spontaneous music. Musicians are always specific, each having their own uniqueness, characteristics and quality. The ensemble aims to allow those different musicians to open up and improve mutually through their interactions, and to be unified in feeling at a higher level of collaboration, developing a dynamic dimension. This dynamism is one of the most important elements to music.

There are performances that, no matter how loud and powerful their sound is, are totally without dynamism. On the other hand, some music achieves that expressive dynamism but is small, gentle and quiet.

What we call dynamism is something qualitative that is produced through the spiritual and physical interactions of the musicians. It is not something quantitative.

Because it can be produced through different vibrations and interactions between the members, as well as through deep and plentiful exchanges between feelings and minds. When these exchanges are one-dimensional, even aggressive performances can be absolutely devoid of dynamism.

Great performances are abundant with dynamism. You cannot produce this dynamism simply by mastering some technical skills, developing responsiveness, or rehearsing a lot.

You have to truly recognize the idea of performance in order to make this dynamism happen, and you need to know specifically what the true function of performance is, and what a true ensemble is all about. You also need to know about body, mind and vibrations, and the roles they play in interactions and performances. You must establish an understanding and rapport for activating mutual relationships in order to be able to produce this dynamism. And in order to acquire this understanding and rapport, you need to have training and a practice based on the exchange of vibrations.

On spontaneous music

My ideal music is truly spontaneous music. I have been working toward this spontaneous music for so long. Frankly, I haven’t yet achieved perfectly spontaneous music, regrettably. I am trying my best, more than anyone, to be spontaneous, and I believe I have spontaneity. However, in order to produce what I call spontaneous music, we have to establish absolutely new and open human relationships between the performers who play together.

Around the time of the "October Revolution in Jazz," some groups and musicians aimed for this spontaneous music, but we could say they all fell short. Occasionally there were times where very spontaneous performances were realized, however they were never developed further.

We cannot achieve spontaneous music without pursuing and sustaining groups (of musicians) who are truly committed to working collaboratively, and making it possible to realize open ensembles. A number of musicians who had previously been trying to play spontaneous music actually shifted away from it because it was so difficult and painful to achieve. “New York Art Quartet”, the group I was part of, was more spontaneous than any other group, but it didn’t last long. Spontaneous music cannot be created without powerful mental strength, tenacity and courage, as well as a continuous group effort. Many people ran away, self-destructed, or shifted their musical direction formally and structurally toward different styles, forms, and conventions.

Whether it was Cecil Taylor or Albert Ayler, that was what they did. For me, authentic Free Jazz means this spontaneous music. For example, spontaneous music goes something like the following: All exist with their own uniqueness, and while all of them, in their respective way, is a self-motivated individual, together they create an open fusion and a collaborative/communal musical horizon, spontaneously, like a natural occurrence, naturally, through performing. As stars fly in the sky, insects chirp on one side, leaves rustle in the wind over here, the river flows over there, different things occur simultaneously, and as if they were going to unfold the certainty of their respective existences through connecting with each other, along with the rhythm and order of the universe and the earth, with the rhythm of nature, music is created. And all of them respectively project the lights of their own uniqueness, exchange with one another, and continue with each other, without any contradiction or repulsion. We therefore cannot produce spontaneous music unless we agree upon each other’s views of the universe, body, and existence, and share a common spiritual understanding.

When we look at the current situation of America in terms of our spirit aiming for creative, totally free and open music, it feels like we are moving backwards from the time of 1964 or 1970. In this sense I say that, at the moment, New York is becoming debilitated. We have to have creatively energetic power in order to produce something, but it seems to me that people are not interested in the necessity of this real power. Instead people are blindly following their own individual expression. What we call individual expression is just an idea.

What I have been calling for the past ten years is to create truly spontaneous music. I have been trying it with some musicians. One of those musicians, Arthur Doyle is currently not performing due to mental injury. But I will further follow the path to spontaneous music because the greatest freedom is staked on this spontaneous music.

On Japanese musicians and audience

I came to Japan to work with Japanese musicians like this, and this is what I have been doing. All the Japanese musicians that I have performed with were New Jazz musicians, but at first, I was at a loss. I came here imagining that Japan was a country with more of a spiritual culture than other countries, and when I came to Japan I realized that was in fact the case. However, it seemed like the Japanese musicians were not so deeply involved with spiritual matters. In the course of performing together over time, I was able to clearly understand particular qualities of each musician, and establish growing relationships. The Japanese musicians who I know are even more aggressive than musicians in New York, however I also felt that they haven’t thoroughly acquired a common foundation to work collaboratively towards real music. You need to keep persevering in order to acquire this foundation itself. However, I rather thought it was also unfortunate to discover that, as in America, here there are musicians who are engaged in the musical rigidity of western music. I particularly selected Takagi (Mototeru), Kondo (Toshinori) and Toshi (Tsuchitori Toshiyuki) as my fellow performers out of several musicians because more than the others, they had modesty, devotion, and single-minded determination, characteristics needed to work collaboratively. In fact, Takagi’s breathing was more supple than anybody else's, while Kondo’s breathing was more powerful than others. And Toshi had more flexibility than anybody else. Although this is true with both audience and musicians, I thought they all had in common that they would be more relaxed. This state of being relaxed is absolutely essential in order to receive different vibrations of all things happening, and to interact with the vibrations.

To be relaxed and to be easy-going are totally the opposite of each other. I hate analogies, but if I was going to use an analogy, I would say that I believe that we must play music to realize big love. No matter how much effort I put into acting on love, if my fellow musicians stiffen up, either by just being dumbfounded, or get scared, and just stand there and watch, the love relations will not develop. Because love can be produced when we mutually act on it. Japanese audiences are always a bit tight and too passive. As is the case with musicians, where there is passivity, there is no dynamism or love to be created. Each person should be a single subject as long as the person is living their life, and love can never happen unless this subject makes more conscious effort to work on it subjectively and positively. This is true with any authentic performance or music.

At a concert I always try to feel the vibration specific to the place, the specific vibration of each individual in the audience, because I always play for specific, individual audiences, and in order to make a performance for each person, I need to feel and acknowledge their individual vibration, and transmit my vibration as a reaction to that vibration. I use different techniques and play polyrhythm or polymeter with my drums in order to live better with one another, to unfold a piece of music more positively within a specific interaction and exchange. The vibration in our mutual interaction changes every second of every minute. That is why performance must always be continuous and dynamic, and keep changing at the same time. This is why improvisation is inevitable, and this is the meaning of improvisation.

Music exists for the purpose of living better, mutual higher development, opening each other up. That is why music is personal, but at the same time communal and social. True living music is impossible without keeping this in mind. Stubbornness or egotism is the enemy of this living music.

The purpose of living music is for people to become lively. To achieve that goal, we have to eliminate all negative thoughts and actions.

We have to be more self-motivated, be more proactive and be more aware in order to make freer and more open music possible. And music can be created within a shared and communal place and time where musicians and audience interact with, influence, and exchange with one another.

●

In this second installment of the “Milford Graves Collected,'' practically the entirety of my task was to compile the many statements of this extraordinarily talented musician, and then allocate as much space as possible to them. Therefore, regrettably, my own essay on Milford, my more subjective project, was not possible this time. However, that part of my own work which I couldn't realize here was also significantly involved in the compilation of Milford's discourse, and I look forward to fulfilling that task of recapturing Milford more specifically in the third installment of the “Milford Graves Collected.” I have to say that, throughout this project so far, an overview of Milford has not yet been fully highlighted. However I think I was able to offer a "collection [of his statements]" which presents Milford’s singularity as sincerely as possible. My experience with Milford in its depth and breadth cannot be surmised through other means. However, through this project of reconstructing Milford's discourse, I would say, taking a step towards clarification, it has attained a more concrete manifestation. Therefore, I now feel clearly that I would like to offer the result of this project, this ‘collection,’ towards the possibility for each and every reader's experience.

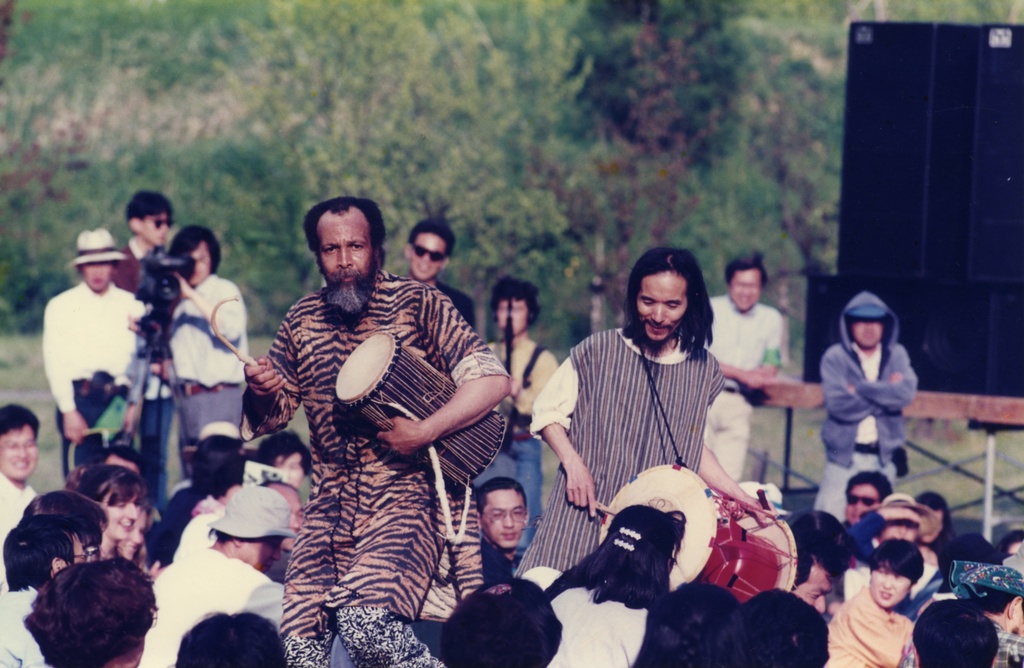

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves and Toshi Tsuchitori, Japan, 1977. Color photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Charlie Steiner, Milford Graves Solo Performance at the Kai-Momagatake Shrine, 1988. Color video, sound, 25:32 minutes. Courtesy of Charlie Steiner, Vagabond Video.

Aki Onda, Milford Graves and Min Tanaka, 1985. Courtesy of Aki Onda

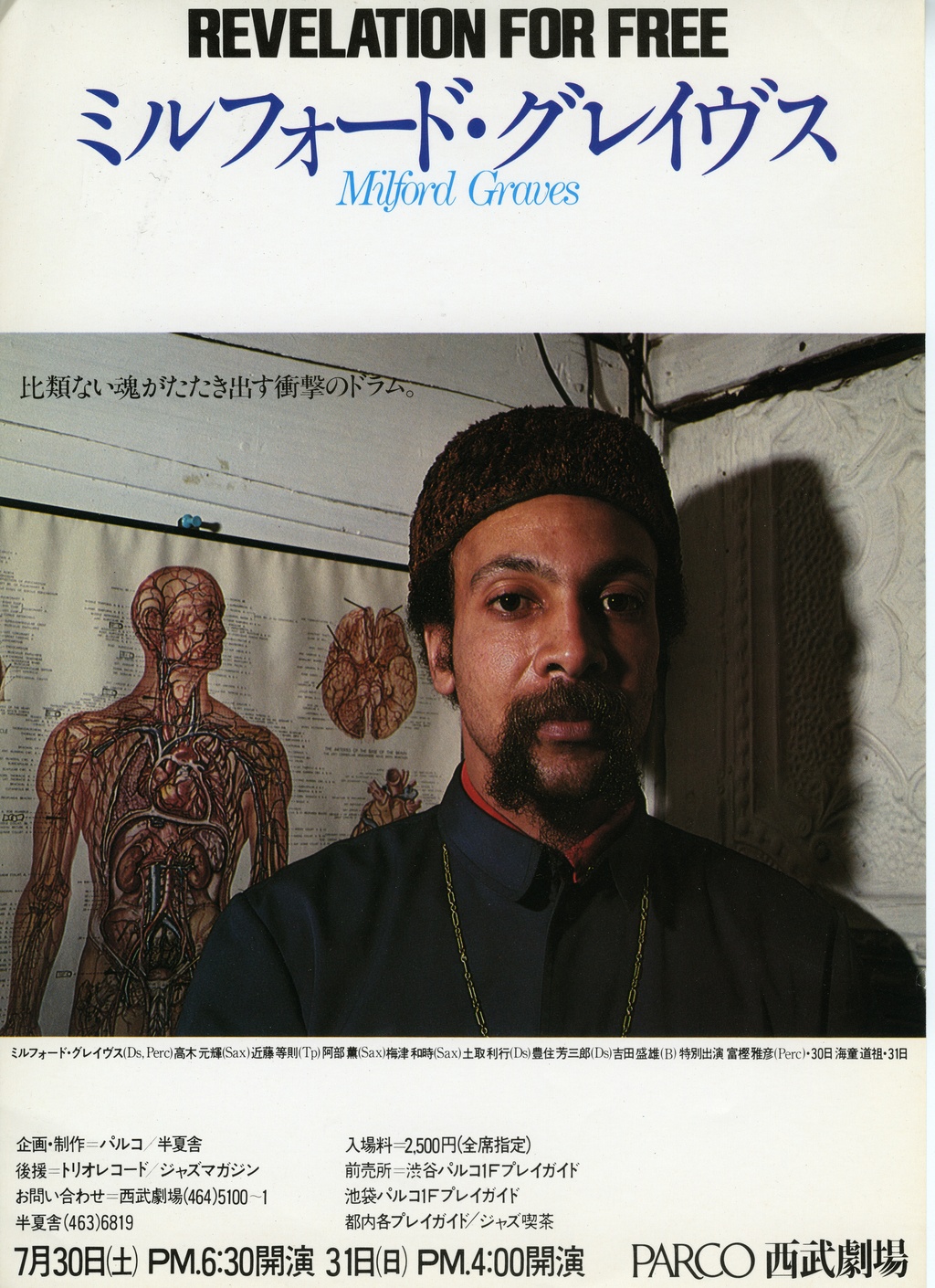

Milford Graves, Revelation for Free, 1978. Tour flyer. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves with Toshi Tsuchitori in Gujo, Japan, 1993. Color photograph. Courtesy of Toshi Tsuchitori

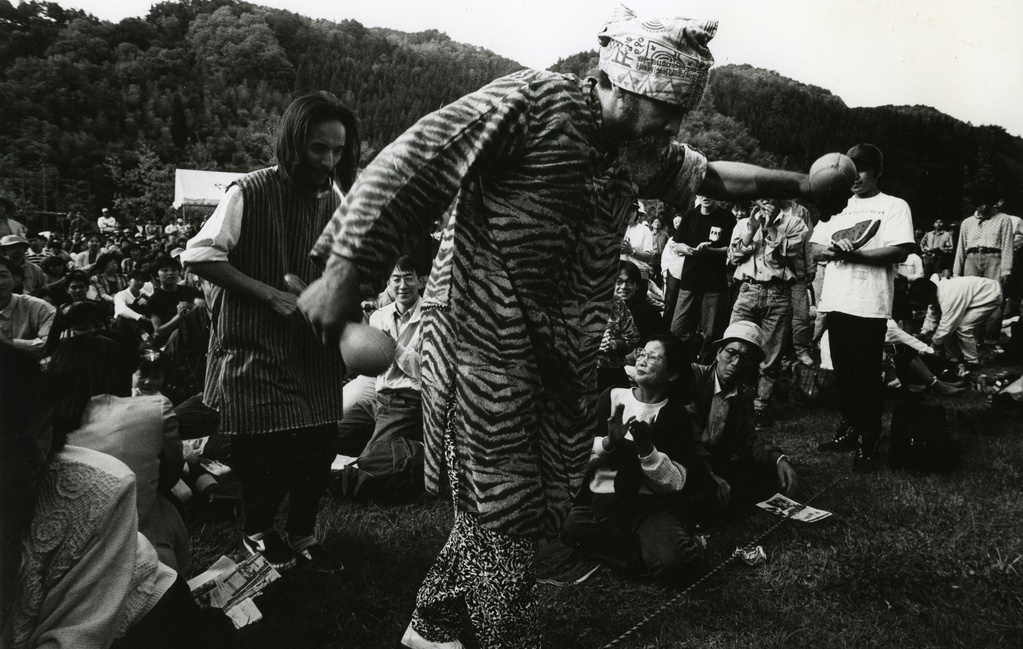

Eimei Uchiyama, Milford Graves with Toshi Tsuchitori in Gujo, 1993. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of Toshi Tsuchitori.

Toshiro Kuwabara, Milford Recording with Aida and Toshi, 1977. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of Toshi Tsuchitori.