Demonstration of Needling Technique, c. 1980s. Color video, 17:13 minutes. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Tangible Frequency: Milford Graves's Study of Acupuncture

Stella Cilman

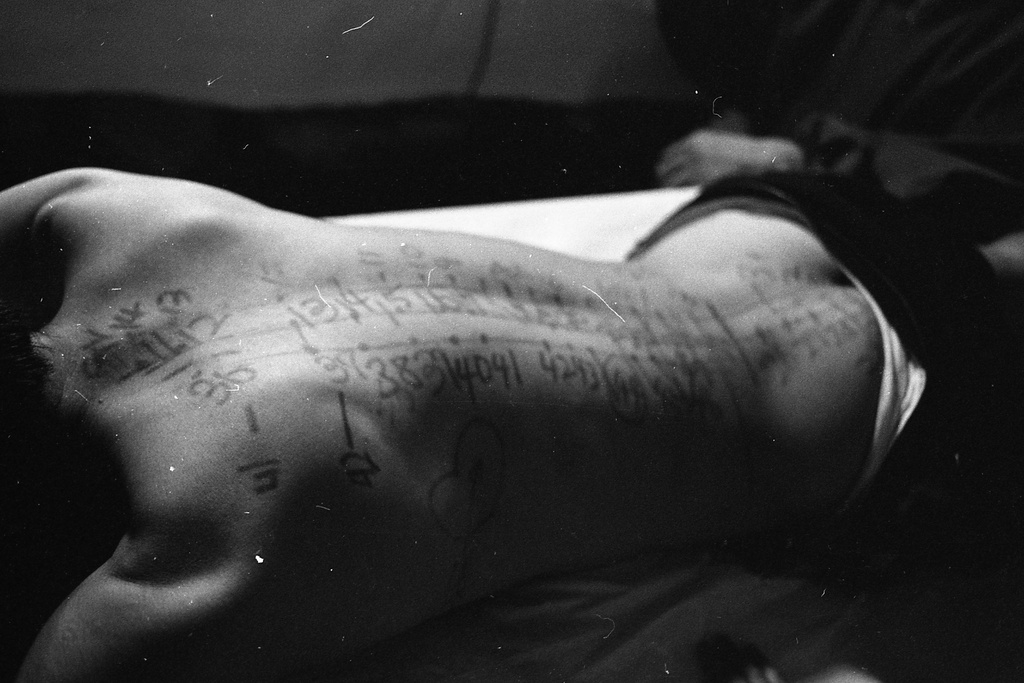

Huddled in his basement laboratory in 1989, Milford Graves and a group of friends, musicians, healers, and disciples held a secret acupuncture session (a practice only recently legalized and heavily regulated in the US).[1] The covert gathering is documented by Graves' long-time student Yuji Agematsu, who, like the healer, trains his attention on exacting points of contact between the body's surface and its interior, capturing the moments of perforation in great detail against soft, receding backgrounds. These candid black and white snapshots depict intimate scenes of collective healing, as individuals insert needles into their own and each other’s bodies, the students often crowding around a single person to watch. In one image, a complex numerological pattern has been inscribed on a man’s bare back as he lays face down on a bed. In another, nuggets of marijuana burn softly atop a group of shallowly inserted needles, allowing the plant's medicinal properties to seep into the body. Taken as a whole, the suite of photographs provides a view into Graves’ private, but community-centered sphere, a space he referred to as the “Center for Universal Wisdom,” and wherein he facilitated a range of transformational experiences.

From an early age, Graves’ profound curiosity propelled him to seek new knowledge through disciplined, self-guided study across a disparate, cross-cultural spectrum of activities and subjects. Growing up in Jamaica, Queens in the 1940s, Graves was surrounded by a myriad of cultures and traditions: the music of Cuban Mambo bands, African movement and drumming, martial arts, and boxing, all of which would later influence his various practices. As a child, he was fascinated by movies about African "Voodoo," particularly the ones where people stuck pins into "voodoo dolls" (despite Hollywood’s exaggerated depictions).[2] Images of the pierced body covered in protruding pins would resonate with his later interest in Nkondi statuettes (frequently referred to as Kongo nail fetishes), wooden anthropomorphic figurines that contained magical and protective powers, which were accessed by "driving a nail or tack into the surface and stirring the life-force to action."[3] Graves collected and displayed these dolls in his basement, and later incorporated them into his multi-media sculptures.

An interest in healing came naturally to Graves. As a child, he would watch his grandfather concoct medicinal remedies from his collection of obscure ingredients, treating people in his community out of his home. The practice of herbalism ingrained in Graves a commitment to the notion of self-reliance, a concept that would become critical to his approach to both healing and music throughout his life. Notions of self-reliance and free thought were also becoming increasingly vital to the evolution of the social movements of the 1960s, particularly within the Black Panther party and as tenets of the Black Arts Movement.[4] Graves was inspired by many Black intellectuals leading the movement, including A.B. Spellman, Larry Neal, and Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones), whom he collaborated with on the iconic first recording of the New York Art Quartet in 1964. In a transcribed research session with his student Paul Austerlitz, Graves relates the foundation of revolutionary political positions to the historical necessity for Black inner determination. He writes, “We were stripped of many things, stripped of the drum. Being stripped of so much taught us to call on our inner resources to survive… so much has been stripped away that they have been forced to go inside their inner selves and totally open themselves up to new levels of consciousness.”[5] In 1966, Graves and pianist Don Pullen founded the record label Self-Reliance Program (SRP), independently releasing a number of duo albums. Announcing the label in a manifesto entitled "Black Music" published in 1967, Graves and Pullen state that they intend to pursue complete liberation from Western systems, using the music to free the mind and body, discarding assumptions about musical direction, and developing their own instruments.[6] Situating creativity, action, and thought as arising from deep within the individual, Graves' multifaceted healing practice attended to various forms of harm with a self-made remedy.

It wasn’t until Graves developed a number of stress-related digestive and intestinal problems in his twenties that he fully committed to a holistic lifestyle. He became a vegetarian, scoured books on herbs and alternative medicine, and began to assist others in diagnosing and treating their ailments. In 1965, he discovered acupuncture incidentally after coming across the word in a book belonging to poet and Jazz critic A.B. Spellman. Unaware of its meaning, he was fascinated by the cadence of the word itself, and felt the inexplicable urge to make it a part of his vocabulary. Graves soon after became engrossed in the field, and, because acupuncture was illegal in the US at the time, he enrolled in a correspondence course with the Occidental Institute of Chinese Studies based in Canada. The course focused on the theoretical aspects of acupuncture, but also sponsored acupuncture conventions for students and instructors where visiting practitioners from all over the world would lecture on different philosophies and techniques. Graves was particularly inspired by the work of scholar Joseph Needham, who used cross-cultural comparison to demonstrate the relations between Chinese and African spiritual and medicinal practices as early as the 10th century. Graves began to make connections between these intellectual and philosophical threads and his own experience and history—conjuring images of the Kongo nail fetishes, African Ritual practices, and his grandfather’s extensive collection of roots and herbs. These connections, bridging physical and psychic space and time, would lay the foundation for his uniquely cross-disciplinary, centripetal approach to healing. Looking towards Eastern and Ancient paradigms that conceived of healing as a mutable and constant (re)adjustment of the mind and body over time, Graves moved away from the Western conception of medicine as the utilization of a singular “treatment” to “cure” a patient. He believed that in Western science, as with European music, there were too many constants, writing "like tempered scales and fixed measures.... where are the Variables? Mathematical equations should have more variables than constants. Constants are limited in that they do not go to deeper levels; they do not move. You do not get spiritual growth when your imagination is dampened."[7]

For Graves, both acupuncture and music operate on principles of “vibration and frequency.” While acupuncture deals with tangible frequency (touch) and music with intangible (of or arising from the cosmos), both necessitate the movement of energy from one point to another.[8] The body, as with the drum, contains a limited number of hyper-energized points that, when stimulated, have the power to rebalance the entire system. The activation of these points heightens consciousness and allows one to “tune in.” Graves was particularly fascinated by the relationship between acupuncture points (Xue) and meridians (Jing Luo), the channels through which qi flow vertically and horizontally, creating an energetic three-dimensional fabric throughout the body.[9] Needham conceived of Jing Luo as non-linear (as opposed to linear) conduits. Drawn to the multi-directional, multi-dimensional nature of these meridians, Graves states: "People are always trying to connect the acupuncture points with linear meridians, but it might not be a predictable situation...If you go into the woods, you will not find a path, but you will be more in tune with yourself. We need order in the world, but we also need non-order. Our bodies have no sense of equal measured time; heartbeats change according to what the situation is."[10]

Graves often used the metaphor of "crossroads" to illustrate his approach to acupuncture. In an interview with WBAI radio host Carletta Walker in the late 1980s, Graves describes crossroads as key points of convergence running across horizontal and vertical planes that contain vital, intense energy. When stimulated, transformational and transmutational things can take place. He believed because there are so few key points in the body (sometimes as little as twenty), a limited number of needles should be used during a session. While on tour in Japan in 1981, Graves had a transformative session where the acupuncturist utilized a pulse diagnosis treatment along with needling to re-calibrate his body, after being warned his energy level was dangerously high. Following this event, he became more invested in Japanese techniques, which utilized very thin needles inserted swiftly and shallowly into the skin, as opposed to the larger, thicker ones used in Chinese acupuncture.[11] In a video that documents his needling technique, Graves begins with a shot of an anatomical acupuncture doll stuck with pins while Tabla music plays in the background, before tracing his hand over the contours of a body, feeling and describing each muscle. Throughout the examination, he identifies four "problem points" in the back, located by the noticeable "twist and jump" sensation felt by the patient during stimulation. He cleans these areas and inserts a barely-visible needle into the skin at about a 45-degree angle. Utilizing the Japanese "pecking technique," he rhythmically thrusts the needle into the dermis with rapid, short-amplitude force.

Always incorporating various fields of knowledge from his studies and his lived experience, Graves' acupuncture practice facilitated an understanding of the interconnectedness between music (vibration), herbs (energy), and the body (heartbeat). In preparation for acupuncture treatment, one must consume a sufficient amount of nutrients, provided by herbs, to avoid a full depletion of energy during a session. And over the course of the session, the healer must know how to stimulate an individual’s key points—their crossroads—in order to facilitate a transformational vibration that lifts the recipient into another realm. For Graves, entering another realm was always the ultimate goal.

[1] In the wake of its legalization in the US in 1973 (1976 in New York), stringent laws were passed to regulate the practice of Acupuncture and Traditional Medicine. In 1972, the FDA classified acupuncture needles as “investigational devices,” and then reclassified them in 1996 as Class II medical devices to be used only by licensed practitioners. See: Suh Y. The regulation of Chinese Medicine in the U.S. Longhua Chinese Medicine, 2020.

[2] Paul Austerlitz, Jazz Consciousness (Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 160.

[3] “Art & Life in Africa - the University of Iowa Museum of Art.” n.d. Africa.uima.uiowa.edu. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://africa.uima.uiowa.edu/media/photos/show/1611?back=chapte.

[4] Neal, Larry. “The Black Arts Movement.” The Drama Review: Volume 12. 1968.

[5] Paul Austerlitz, Jazz Consciousness (Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 160.

[6] Graves, Milford, and Don Pullen. "Black Music." Liberator. January, 1967.

[7] Paul Austerlitz, Jazz Consciousness (Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 170.

[8] "Interview with Milford Graves," Carletta Joy Walker, WBAI New York, c. 1980s.

[9] “Meridians and Acupoints, Jing Luo, Complementary and Alternative Healing University.” n.d. Alternativehealing.org. Accessed November 22, 2021. http://alternativehealing.org/jing_luo.htm.

[10] Paul Austerlitz, Jazz Consciousness (Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 169.

[11] "Interview with Milford Graves," Carletta Joy Walker, WBAI New York, c. 1980s.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, c. 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Milford Graves, Herb Lecture. Color video, 20:46 minutes. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Yuji Agematsu, Acupuncture Photograph, 1989. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.