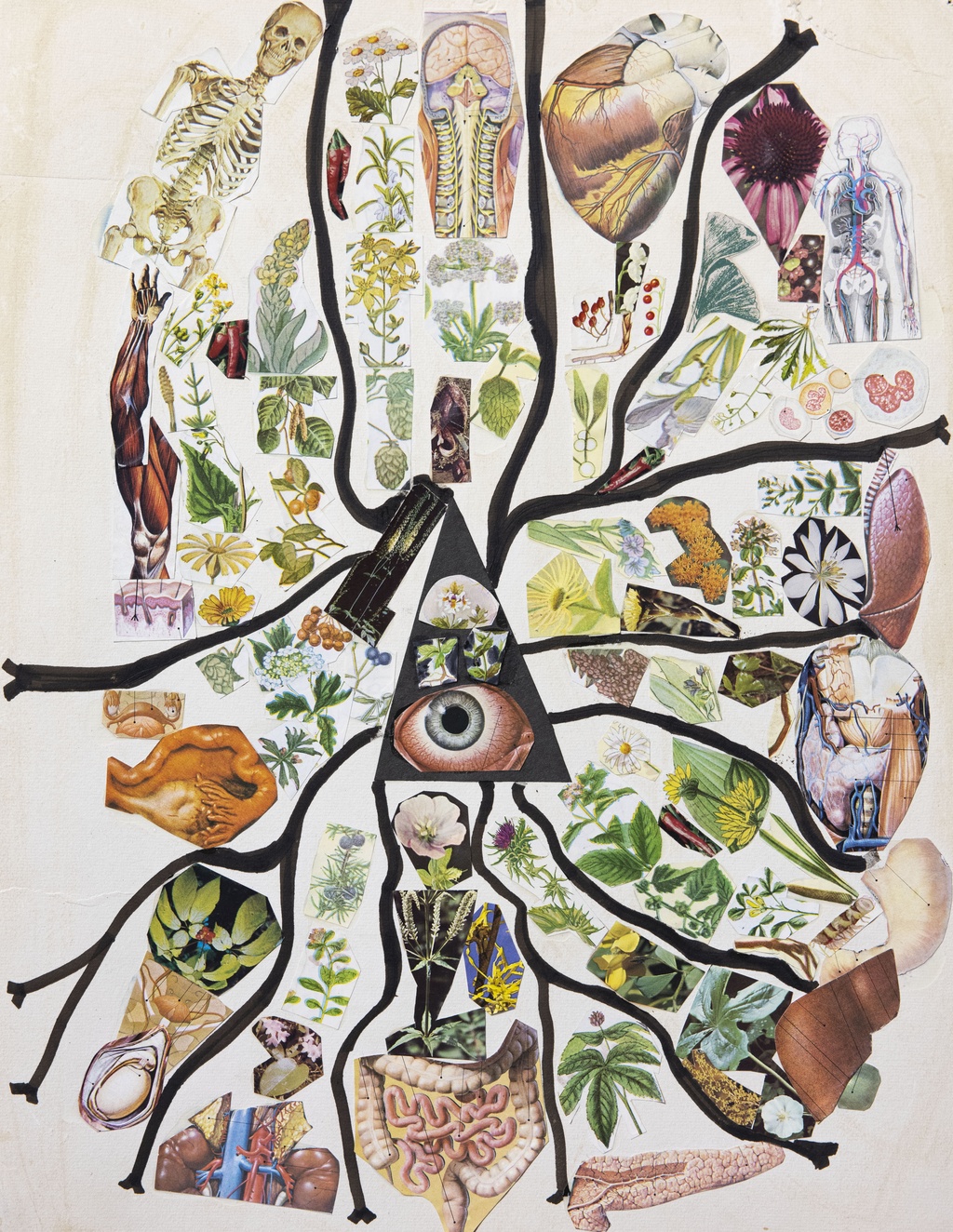

Milford Graves, Collage of Healing Herbs and Bodily Systems, 1994. Mixed media collage. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Breath-Air: Notes on Fundamental Frequency

Danielle A. Jackson

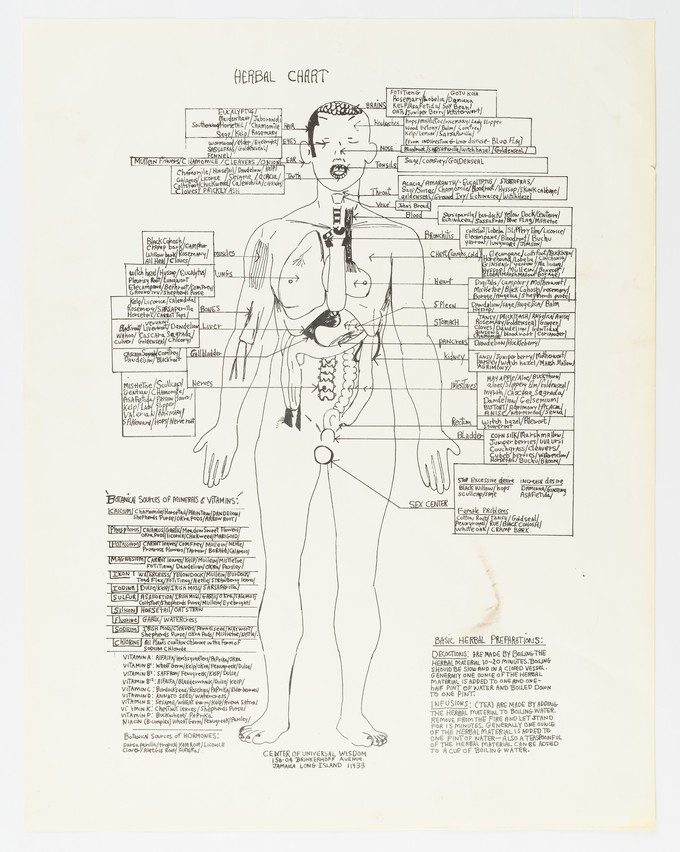

Basic herbal preparations

Decoctions: are made by boiling the herbal material 10–20 minutes. Boiling should be slow and in a closed vessel. Generally one ounce of the herbal material can be added to one and one half-pint of water and boiled down to one pint.

Infusions (tea): are made by adding the herbal material to boiling water. Remove from fire and let stand for 15 mins. Generally, one ounce of the herbal material is added to one pint of water—also a teaspoonful of the herbal material can be added to a cup of boiling water.[1]

A man walks slowly in about six inches of snow in the middle of what seems to be a forest. The trees sway back and forth as the wind blows fervently. The weather looks bone-chilling. Taking long and precise steps, he carries a singlestick or cudgel (like the ones used in martial arts), swinging it from left to right while periodically pausing to enact warrior poses and propulsive gestures. He appears to move with the wind, fully in tune with the element as if detecting its scent or its undulating vibrations.

Eventually he drops the stick and throws his hands up toward the sky in a circular motion, arms shaking with an involuntary tremor-like movement—the right followed by the left. Altering the rhythm and pace of his arm rotations, he kneels, jumps back up, then moves his arms from side to side in clockwise and counterclockwise motions. He breathes heavily, but in a way that feels intentional and composed. His breathing is as heavy and rapid as the wind.

Grabbing tree branches, almost using them as extensions of his own hands, the man moves them in a scissor-like motion. At times, he hides behind nature, then returns, quivering, recalling the immediate and palpable reaction of a body in freezing temperatures. The reality of his actions takes different forms, but what is most acute is the sound—a loud howl, a subtle and measured vocal rhythm of inhaling and exhaling, the buzzing that evokes a fly but ranges over octaves. The sound builds, then falls. The artist slips between different energy forces—a foundational principle of Yara, a martial-arts form that means “nimble” and “flexible” in Yoruba and is comprised of warrior poses, African ritual dance, and the Lindy Hop.[2]

Artist Milford Graves documents himself performing these expressive actions in the 1990 video Movements in the Snow, one of many tapes that record his decades of Yara happenings. An herbalist, acupuncturist, martial artist, and celebrated jazz percussionist who played a great part in ushering in the Free Jazz movement, Graves was both a dedicated student of human anatomy and a master of sound and improvisational forms who manipulated vibrations and frequencies.

In the lower atrium of Milford Graves: Fundamental Frequency, a retrospective exhibition looking back at Graves’s holistic and expansive approach to sound as well as his many relationships and networks, the video Movements in the Snow is playing. Above the monitor is an herbal chart hand-drawn by the artist—positioned relatively low to the ground such that it forces an intimate interaction with the viewer’s crouching body—detailing instructions for herbal decoctions and infusions that heal or otherwise serve as medicine. It illuminates herbs that assist certain organs, bodily functions, or mineral absorption, for example St. John’s bread or Carob for healthy vocal cords; kelp for bone health; dandelion and black root for enhancements to bile flow from the liver; carrot leaves and okra as sources of magnesium, and so on.

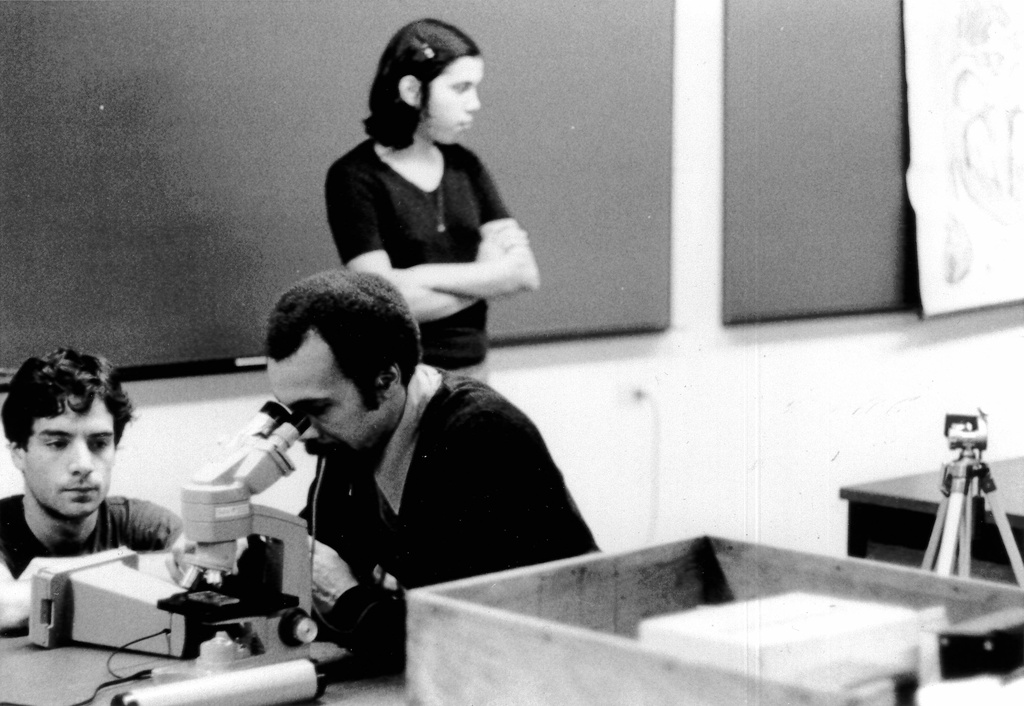

Photographs scattered throughout the galleries by Yuji Agematsu, one of Graves’s longtime Yara disciples, document a secret 1980s acupuncture session at Graves’s home, again pointing to the act of healing by alternative medicine.[3] These can be understood as candid snapshots of the work produced in his laboratory, which he called the Center for Universal Wisdom, where at any given moment he might share knowledge of acupuncture’s philosophies or ruminations on other topics—knowledge that he may have acquired from his travels to Japan or unearthed from the pages of books in his wondrous and esoteric library. Graves was a master of community building.

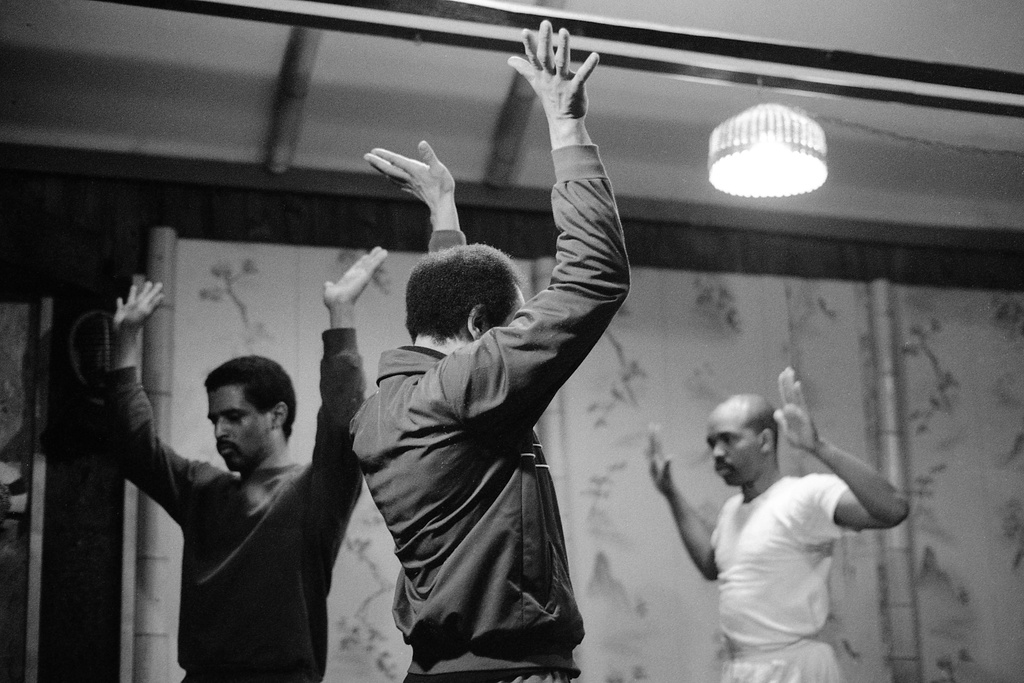

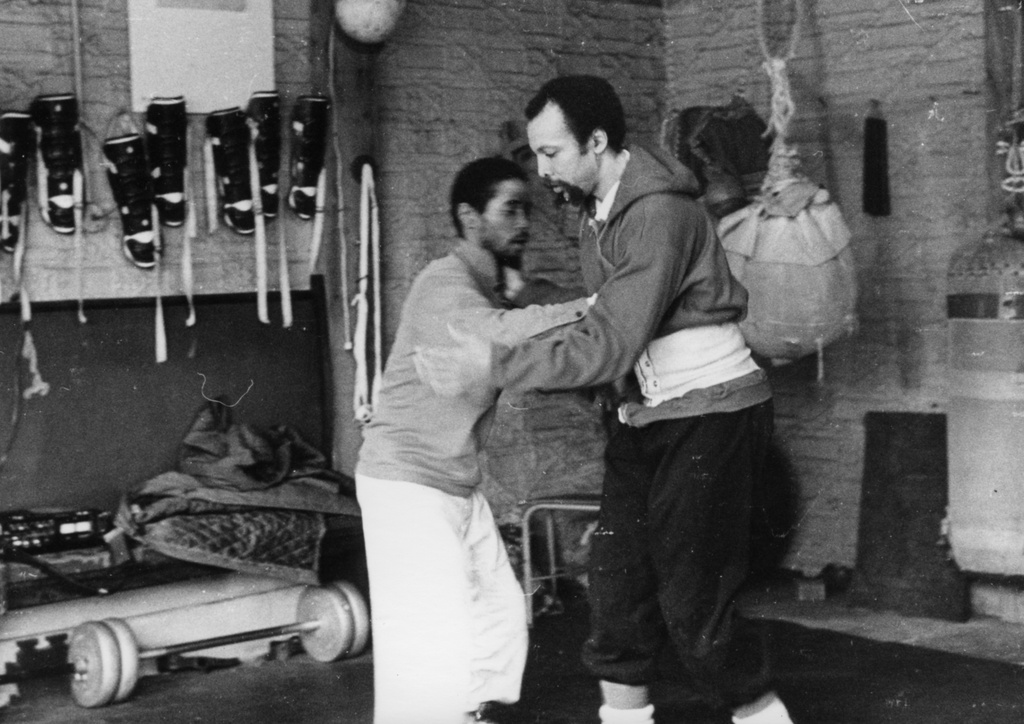

Putting these works in adjacency is a simple curatorial gesture, but one that lays a foundation for broader observations this show tries to illuminate—namely, that Graves’s practice always foregrounded the body’s internal mechanisms and bodily philosophies, whether via scientific recordings illustrated with EKG printouts; animations and sculptures using engineering software to measure, record, and manipulate heart rhythms; movement forms like Yara that Graves practiced in his home dojo; the act of gardening and eating plants to ingest their cosmic and healing energies (Eating in the Garden [1990]); or his exhaustive and intense musical performances with the likes of Albert Ayler, Toshi Tsuchitori, and other experimental jazz musicians who used their physicality and understanding of their instruments to reach the deepest limits of music and sound.

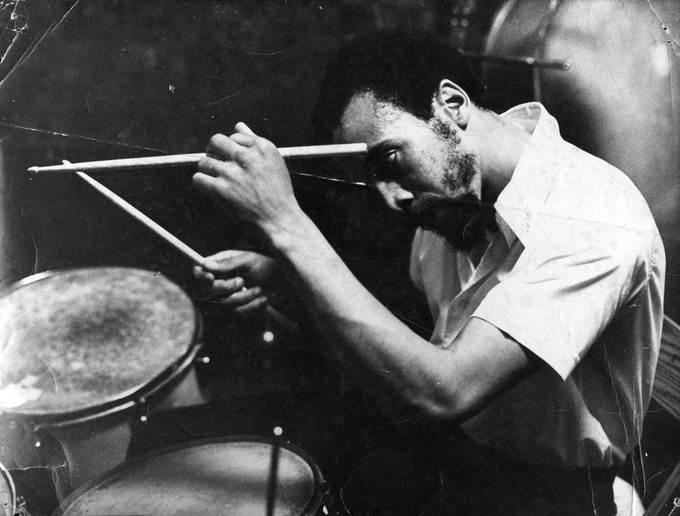

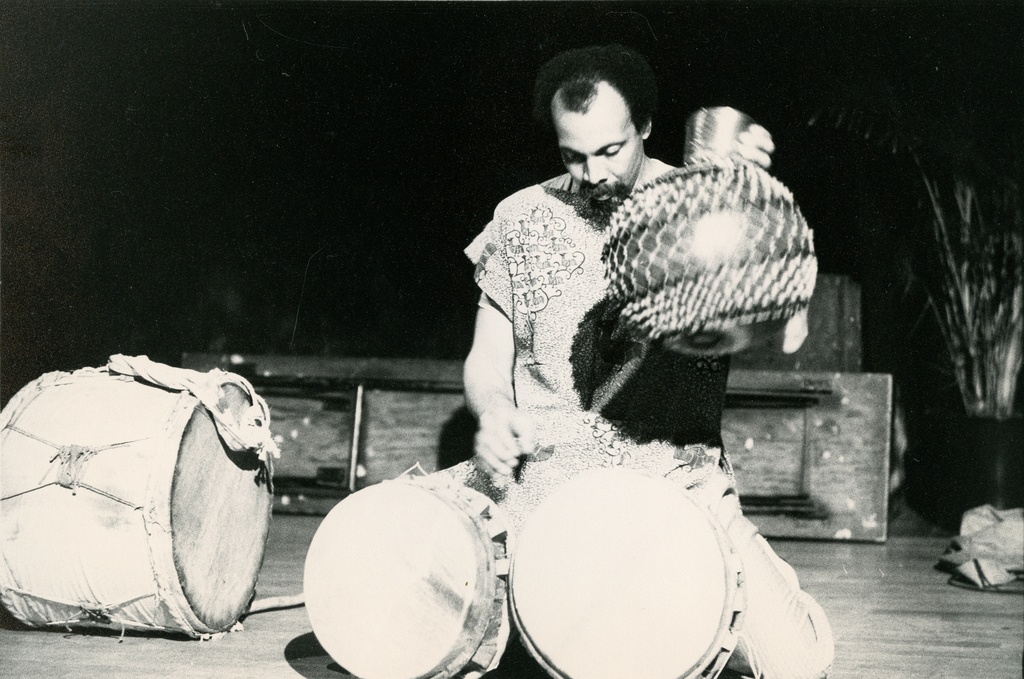

Performing with a colorful drum set—hand-painted in greens, blues, yellows, and reds, and with the bottom drum skins removed to allow for what he called “maximum resonance”—Graves maximized his instrument’s potentiality, amplifying it into a kind of percussion choir that echoed the versatility and nimbleness of Yara. It was a host where Latin and African polyrhythms, Indian tabla, and Japanese gong rhythms could coexist. Circular nodes—a reference to the positioning of the cosmos (north, south, east, west horizons) are etched and marked on the top skins, further highlighting Graves’s view of his drums as a tool by which to reach the cosmos. A critic once called Graves’s drum set “an enlightened communion with wood, metal, and skin.”[4] In extremely intense moments of playing, it is said that Graves would revert to the basic instincts of his hand drumming days; flinging the sticks away, he would play open handed or create bilateral movements with his elbows.[5]

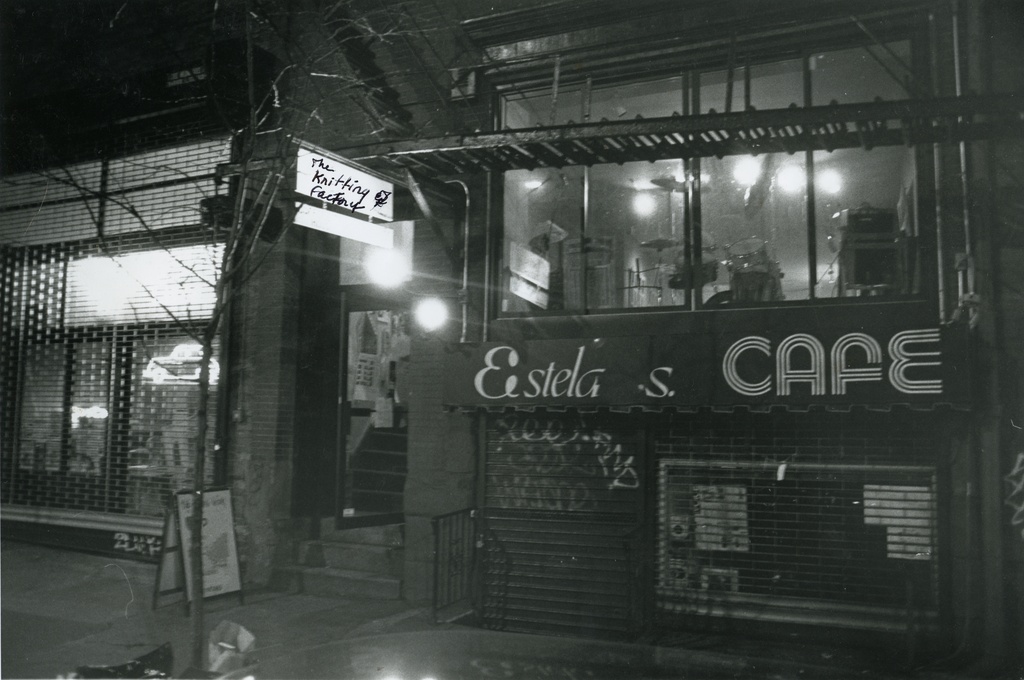

Indeed, his instrument was more than the drums. It was his body and limbs—a full immersion into the depths and heights of what propulsive spiritual energy could produce. One night while performing with saxophonist Albert Ayler at Slugs’ Saloon, a jazz dive in New York’s East Village, Graves famously played with such intensity and rigor that fellow musicians in the crowd jokingly remarked that he couldn’t possibly maintain that energy for another set. But Graves went on for five nights straight, three sets a night, only finally collapsing when tapping into the deepest level of his internal rhythms had truly exhausted him.[6] Slugs’ attracted a range of people—music enthusiasts, writers, poets, intellectuals, and avant-garde jazz musicians, from Amiri Baraka (a Graves collaborator) to Sun Ra to A. B. Spellman. A kind of existential experiment in human interaction, Slugs’ emerged from its owners’ (Jerry Schultz and Robert Schoenholt) enthusiasm for spiritual mystic and composer George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. Guridjieff’s teachings identified a “fourth way,” an engagement with mental and physical activities that could bring about a total alteration of consciousness.

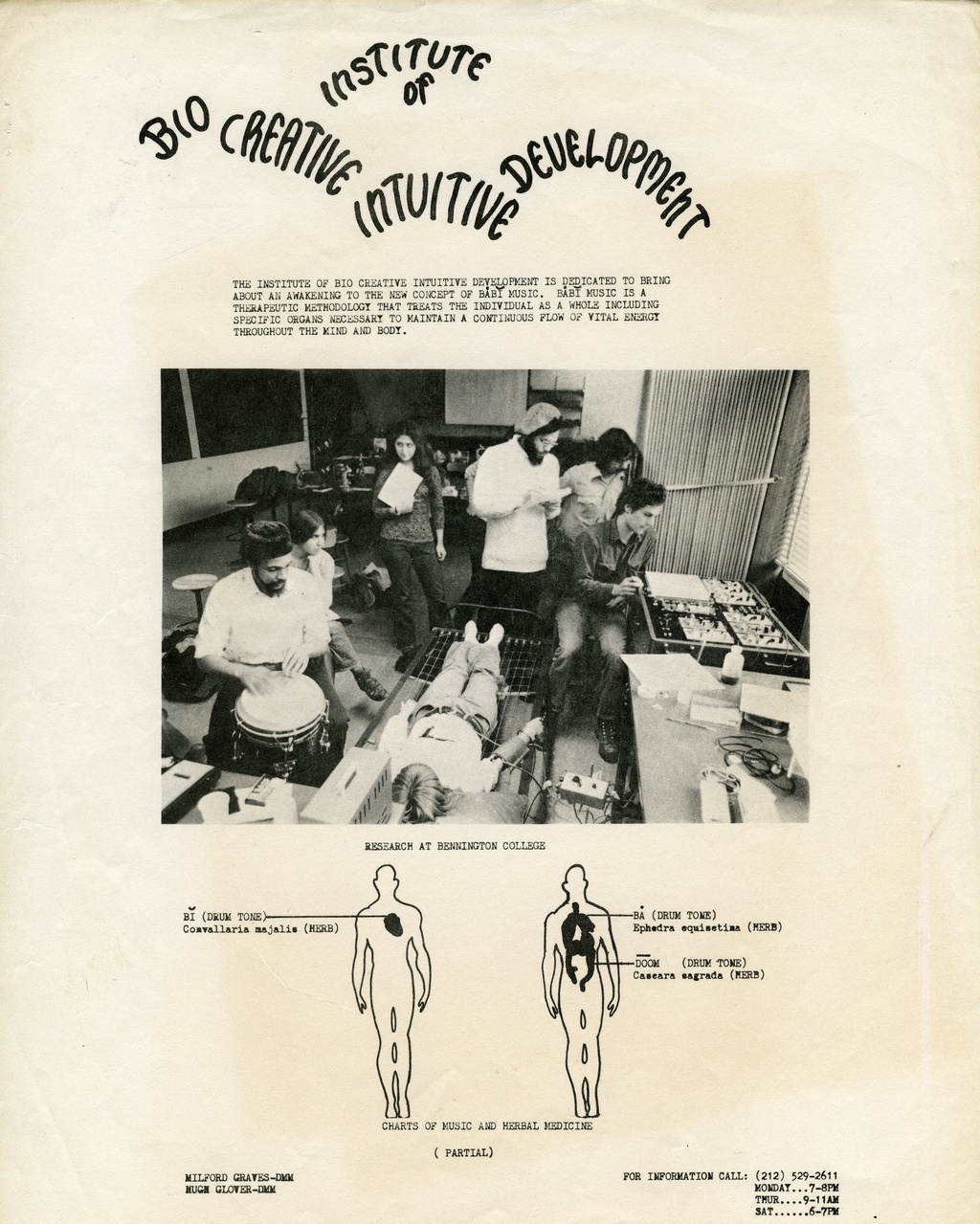

It’s uncanny how very many musicians like Graves, who had developed their own intellectual philosophies around spirituality, cosmology, and fundamental frequencies, found Slugs’ a haven for their creative expressions. But Graves embraced the idea that music extended beyond a single concept of playing or site of musical communion. Years later, he developed what he called Bäbi music, a concept rooted in recognizing the drummer as an influential improviser but also “a therapeutic methodology that treats the individual as a whole, including specific organs necessary to maintain a continuous flow of vital energy throughout the mind and body.”[7] Broken down, bä is the drum tone that activates the respiratory energy, and bi is the drum tone that activates circulatory energy. According to Graves, the frequencies of Bäbi music are in tune with the forces inherent in all living things and responsive to all living stimuli: Earth and cosmos.[8] Graves’s philosophies spanned the space of concert, home, and classroom; in the late 1970s while on the faculty at Bennington College, he held a research session or class entitled the Institute of Bio Creative Intitutive Development. Students would get their heartbeats recorded and Graves would play Bäbi music to bring about an awakening to the music and its healing properties.

Graves’s practice was multifaceted, tapping into sound philosophies that extended far beyond the music industry and into everyday life. Acupuncture, herbalism, gardening, polyrhythms, and so much more were all fluid expressions to Graves that blended seamlessly in his persistent search for fundamental frequencies.

[1] Milford Graves was a skilled herbalist and dedicated much of his life to seeking a keen understanding of the fundamental and internal rhythms of life and the body. This language comes from a handwritten guide that he gathered as part of the Center for Universal Wisdom, one of many laboratories in the artist’s home.

[2] The Lindy Hop is an African American social dance associated with the culture of swing-era Harlem in the late 1930s and early 1940s. A hot and hip dance, the Lindy is (like Yara) a fusion of many dances, including jazz tap and the Charleston, and was popularized by the singer Josephine Baker. The form is incredibly acrobatic and high energy, with dynamic twists and turns that are improvisational at heart. It combines elements of solo and partnered dance.

[3] These acupuncture sessions were carried out at a time when the practice was not yet legal in New York City. Graves taught techniques to students with a Japanese physician who was visiting. Some of the attendees were his students from Bennington College. This is one of many happenings that Graves hosted in his home—again part of the Center for Universal Wisdom, which also was home to his herbal studies.

[4] Hank Shteamer, “Interview: NYC Percussion Legend Milford Graves,” Red Bull Music Academy, June 4, 2015, https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2015/06/milford-graves-interview

[5] Ben Young, “Call It Art: New York Art Quartet, 1964-65 (Burlington, VT: Triple Point Records, 2012), 45.

[6] See Milford Graves on Albert Ayler, WKCR audio recording with Mitch Goldman and Andy Rothman, July 13, 1987, https://mitchgoldman.podbean.com/e/bonus-19870713-andy-rotman-on-milford-graves/

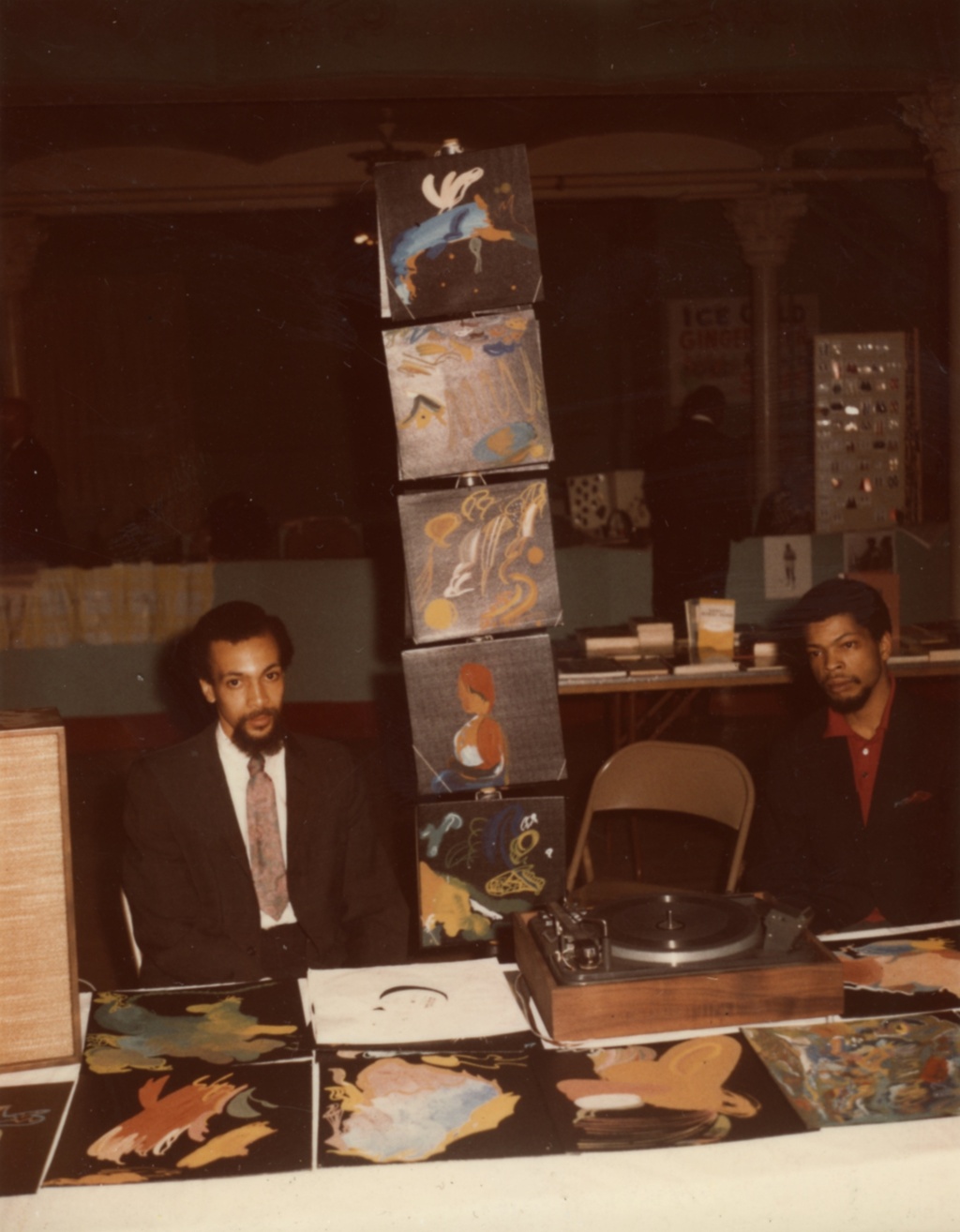

[7] Handout for Institute of Biocreative Intuitive Development, 1977, Bennington College, Black Music Division. They called this event an awakening of Bäbi music as a concept. On this occasion Graves released his groundbreaking LP Bäbi through the Institute of Percussive Studies, founded by Graves and Andrew Cyrille. Years earlier, Graves founded the label Self-Reliance Program with pianist Don Pullen. An alternative to mainstream labels, it was intended to protect artists from exploitation and to celebrate the ingenuity and creative energy of musicians without limitations, much as with the Institute of Percussive Studies.

[8] Unreleased recording of Graves discussing the concept of Bäbi music, 1977, courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Flyer for Institute of Bio Creative Intutive Development, 1978. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Photographer unknown, Milford Graves and Don Pullen with handpainted LPs, c. 1970s. Color photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Photographer unknown,Yara in the dojo, c.1970s. Black and white photograph. Courtesy the Estate of Milford Graves

Photographer unknown, Practicing Yara in the dojo, 1976. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Milford Graves.

Lona Foote, Portrait of Milford Graves, New York, c. 1987. Black and white photograph. Courtesy the Photo Estate of Lona Foote.

Lona Foote, The Knitting Factory, c. 1987. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Photo Estate of Lona Foote.

Lona Foote, Milford Graves and Famadou Don Moye, c. 1987. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the Photo Estate of Milford Graves.